what beauty could come of creatively, ardently processing one’s emotional life. She was a revisionist — Creative Director of one long lifetime sized photo shoot. Her archives are too neat to be true reflections of our lives. All the good parts are excised - cut up and away with squiggle scissors and exacto knives. Ugly shrubs and angry faces plastered over with quippy slogans on textured cardstock and puffed glittery stickers accenting the least interesting aspects of our lives then. CHEER! DANCE! HONOR ROLL! BACK 2 SKOOL!

I am the opposite. My archives an are heavy and nonsensical. They are screenshots of precariously preserved half thoughts, untitled iPhone notes, pixelated fossils zoomed in so close you may not even be able to make anything else out other than a color, an ambiguous shape, the shadow of a person. I rely too much on my own memory to infuse meaning into them, which has failed time and time again. My archives live as their own entity - and like all other things that live they break and breathe and die over and over again.

I’m fascinated by archives. My favorite places have always been the cool spaces between stacks of books, the corners of people’s living rooms where their family photo albums collect dust, printshop backrooms. I’ve always loved the musk of old paper, and the sharpness of ink and glue. I’m far too interested in how paper holds heat the same way skin seems to (don’t judge, I’m a writer, and as such, apparently its necessary I get worked up over making magic out of things no one else even notices).

In addition to the physicality of archival materials, the entire concept of archiving has never failed to stir up in me an old, almost ancient, sensitivity to romance. The way I see it, what could be more romantic than infusing into an item the transient — memory, vigor, feeling? To love life so much, you feel as though you must sew meaning into little bits of paper and cloth or hold onto chipped china.. the way we infuse things with so much love is so immanently human, it’s really not unlike having a pulse. Even minimalists are afflicted. Their commitments to sustaining life with a singular, favorited item is just as romantic as the home-librarian.

I have spent most of this summer (or maybe, actually, its been the whole year) stuck in absolute stillness, trying to figure out what the hell I’m going to do with the next stage of my life. I’ve tried on a few new lives in the relative obscurity of my near-invisible Instagram account and in my new home (Las Vegas). But they all stunk. And in my desperation to make something, move something, do something, I’ve returned to my favorite place. I’ve returned to studying the archives of my life.

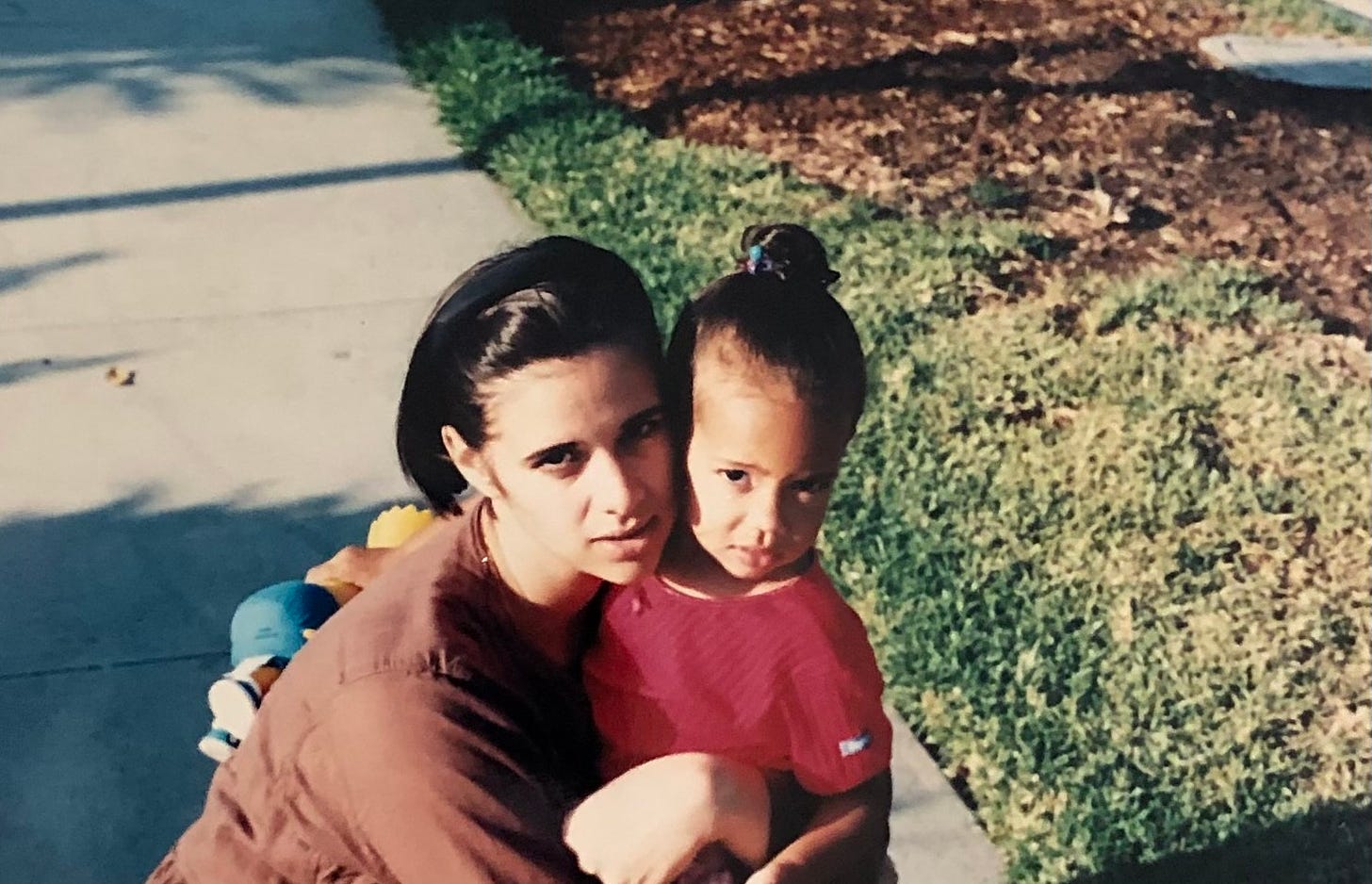

Pouring over one of many baby photo albums my mother constructed while simultaneously fingering through old bullet journals, I was reminded of exactly who I am - not who I have played, the roles I’ve slithered in and out of, but the precise essence of my personhood, the little ball of light I seem to keep abandoning in search of the fulfillment of some empty promise of something ‘greater’, something ‘out there’, separate from me. That’s what happens when you are raised by a revisionist. The shredded edges of you are never worth holding, safeguarding — you learn to treat them like the asymmetrical shabby shrubs in the corners of your photos. You cover them up. You excise them from your consciousness (our therapist friends out there might refer to this as having a disorganized attachment style).

Checking out Hyperallergic a few weeks ago I came across this cool piece — *Why Depressing Art is Good For You* — that got me thinking first about the role of nihilism in art, but perhaps more importantly to my own journey out of the dark pits of depression, what value we derive from paying attention to the binary of sad - happy, or even good - bad, especially in creative work. The article itself posits that depressing art can give us hope and inspire us to be better. Brinkhof writes, “Depressing art can still make a positive impact on the world. Ilya Repin’s 1885 painting “Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan” comes to mind, as do Wilhem Brasse’s photographs of German concentration camps. Both artists show where the darkest human impulses can lead us and inspire us to be better.” We often hear this same argument for why reality tv is not the scourge on our cultural development previous generations accuse it of being. But what is more interesting to me is not just the fact that creativity helps us manage our mental health, it is the *why*.

Developmental psychology research shows (see: the work of Robyn Fivush and Widaad Zaman, Feminist Psychological Theory, Narrative, and Diary Studies) ) that inner narrative making and narrative sharing are key inborn processes for our neurobiological and social development. It’s how we develop our sense of self, without which we have no basis for which to make decisions about how to care for ourselves, what of ourselves is worth fussing over, and what of ourselves is worth sharing with one another to make the bonds that keep us seen and safe. We reinforce those stories by making art and archiving our lives to have tangible representations of our inner narratives; to have something to show and share with others when words or telepathy fail (as I’m writing this, I’m realizing that trading Pokemon cards makes way more sense to me now that I’ve clearly identified the value of things and I should probably apologize to my brother for making fun of his attachment).

This is the medicine of archives, personal and communal — they help restore all those necessary bits so you have a shot in hell in grounding back down into the truth of who you are (or, in the case of familial and communal archives, who we are). I haven’t quite wrapped my head around how to describe with full clarity the dangers of not knowing who we are, but I know its dangerous. I’ve felt it; I’ve lived through my own life falling apart too many times to count and I’ve seen it do so with full understanding that the pin pulled, the start of the avalanche, has always been my failure to remember — this is self-abandonment.

I have felt oftentimes like to be a portrait artist and my practice of remixing and archiving through a creative practice doesn’t feel resonant, doesn’t feel like enough. My contemporaries who are highly ambitious and well represented in the professional realm are aiming to address these massive ecological issues, expand minds, be bold and daring and cutting (or, have otherwise really gotten a handle on just being very very cool and therefore highly marketable) and I’m here in my little corner in the middle of the desert seeing if my small practice of making myself feel seen and beautiful and worthy could fit into or dare I say aid in all of that other big world changing stuff…

Reflecting on the process of making and protecting archives, I drove myself kind of nutty trying to differentiate between art making and narrative preserving. I’m sure I’m not alone in the crazy-making self-flagellating compulsion to map out every point along the creative journey to prove (to myself and to others) that I am in fact a bonafide artist and not a lazy, talentless hack. But the truth is, that art making as we traditionally view it and archiving are inseparable — fraternal twins.

In my self-flagellation (“I make such shit art,” “Who would want this?” “This is so boring, anybody can scratch a monochromatic portrait into Procreate or take an off-center, high-noise self portrait on their iPhone!”), I was telling myself, if I can pinpoint, extract and articulate why people make anything creative, I can distill this into a booming business and forever be cemented with the rest of my heroes — all those gallivanting, bourbon-drinking, deep-feeling fanatics of the obscure and esoteric. But in the (ridiculous) answer crafting, I realized what I as really doing was this: market researching & brand strategizing — ew (no offense intended if this is your thing, but it is very very much not my thing). And the answer to why my work was feeling flat, silly, uninspired, was not because I was falling victim to the same kind of avoidance my mother fell prey to, but rather because I thought there was something rapturous to meet beyond the practice of archiving. There isn’t. The magic is in the noticing and recording what is there — we make magic out of the mundane that swirls all around us. Where my mother could only attune to that magic by compulsively recording how perky she was at 22, I made my way to playing with magic by recording the things she missed. The things nobody showed her was really worth recording. I write of the way she smells, the words that fell out of her mouth I make poetry, the disdain we had for each other made more palpable by making it into metaphor with dark ink and ripped newsprint. Neither of us are less creative than the other. I make art. And so did she. We have both been archiving two sides of the same coin for decades, trying to remind each other of who we are. As much as I wished growing up that she had allowed her art and archiving to make her more curious to meet herself deeper and deeper, over and over again, that just isn't part of her story. I’m okay with being here to fill in the gaps.